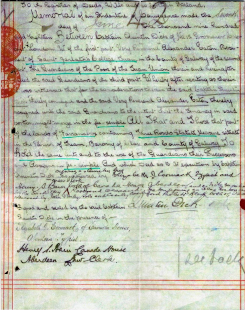

One of the few joys of reading the old title documentation of Irish land transactions are the curiosities that often emerge from them. By Deed dated 17th June 1917 a small parcel of land was sold to the Guardians of the Tuam Workhouse by Captain Quentin Dick, holder of the Fee Simple, or ultimate title to that land. As appears on that Deed (see below) one of the Dick family residences was at Grosvenor Crescent, Belgrave Square, London, part of what is known as Belgravia, a neighbourhood where only the very wealthy have ever been able to own a house.

Those old enough to be devotees of the vintage television series Upstairs, Downstairs will recall that the fictional Bellamy family lived at 165 Eaton Place. The list of notables who have lived there is substantial and diverse. Today the Russian oligarch Roman Abramovich who owns Chelsea Football Club, has a large property on the corner with Belgrave Square.

Quentin Dick was a 'toff' with a family tree and wealth which guaranteed his privileged place in society. Like so many who occupied such a position, his family had been owners of significant tracts of Irish land. Indeed, Dáil questions in March 1946 (footnote 1) dealt with the delayed disposal of the Captain Quentin Dick Estate by the Land Commission. The family always combined its wealth and position in society with the presence of its males in the forces of the Crown. There have always been Dicks in the British Officer Corps.

The 1917 transaction was a small one, involving a plot adjoining the wall of the Tuam Workhouse. The parcel of land in question was in possession of one of the sub-lessees of the land to which the Captain held ultimate title. For some years the Guardians of the Tuam Poor Law Union, had paid a rent of Three Pounds a year for this patch of land and a further Six Pounds a year for an easement over it.

The easement in question was permission to have the raw sewerage from the Workhouse flow out and spread over the land in question. It is unlikely that from within the perfumed urbanity of Eaton Square, Captain Dick was ever aware of this unusual and somewhat indelicate arrangement over his land.

The need for this arrangement was caused by the collapse of the sewerage system of the Tuam Workhouse. Completed in 1841 under the direction of the Poor Law Commissioners' chosen architect George Wilkinson. The Tuam Workhouse had a complex series of tunnels which acted as a drainage system. By the early twentieth century this no longer worked efficiently or at all and the end result was an open cess-pit outside the Workhouse wall, which was later 'covered'.

Up until the day they were abolished, the Guardians of the Tuam Workhouse were constantly threatened with legal action because of the odour and nuisance which this caused locally. While it may be incidental to the central story of Tuam, the Workhouse, a spanking new piece of Victorian construction, though completed in 1841, remained closed until the horrific year of 1846, the very height of the Great Famine. The reasoning of the appointed local Guardians was simple, if we don't open it, we won't have to raise the Rates to pay for it. While the treatment of the Irish people by the British Parliament during the years of the Famine, has coloured the traditional view of perfidious Albion, the good burghers of Tuam had form, long before the creation of the Mother and Baby Home.

In fact, the Poor Law Commissioners based in London had to make an application to the High Court, for an Order of Mandamus, compelling the Tuam Guardians to open the doors of the Tuam Workhouse, to the starving and dying of the town. When it did open, the Tuam Guardians continued their policy of strict economy.

While in normal times entry to the Workhouse was the last refuge of the destitute, at the height of the Great Famine, it was the last hope of those weakened by hunger in ever-increasing numbers. The mortality rate of the inmates was therefore barely less than that among those who could not gain entry, to this last hope of survival. In keeping with their policy of economy, the Tuam Guardians buried the dead in pits within the Workhouse walls, despite the proximity of a cemetery. The cost of a burial plot or coffin it seems, could not be afforded.

Once again, the Poor Law Commissioners had to step in. Because of fear of contagion caused by the disease which attended on so much human misery, they prohibited any burials within the Workhouse walls after 1849 and notably, demanded that the dead have at least the dignity of a coffin.

In 2012 an archaeological dig was required during waterworks being carried out for Galway County Council when a series of graves were uncovered at the junction of the Athenry Road. The remains of 48 persons, adults and children were found. All had been buried in coffins, adults and children alike. These remains were dated as being from the Famine period and are unlikely to be the only human remains from that time in the locality. Regrettably, the 2012 discovery was after 2014, used to tout the suggestion that the remains of the Tuam children, were Famine victims. Thankfully, that nonsense is utterly discredited.

During the first years of the twentieth century, the Tuam Herald conscientiously reported the meetings of the Tuam Poor Law Guardians. For almost a decade, it recorded the most acrimonious, unspeakably bitter and pointless arguments on how to deal with the problem of its drainage system. No attempt at caricature could come close to the reality that emerges from the actual public record. The Guardians were an unlovely lot.

Ultimately an effort was made to construct what today is described as a septic tank, which was covered. In the best tradition of the Tuam Guardians it was done on the cheap, inmates of the Workhouse itself being pressed into labour on the project. This solution was arrived at because more extensive works were deemed too costly. This was what remained in place when the place was finally abandoned as a Workhouse in 1922. However, as is widely known and documented, the Free State Army occupied the buildings as a barracks until sometime in 1925, before making way for the new Mother and Baby Home.

What is not generally known is that the Army moved out because it constituted a health hazard for the soldiers (footnote 2). In March 1925, the local Commanding Officer sought 35.10s for remedial works because:

“The sewage disposal plant having been a number of years without cleaning or overhaul, the whole plant is in need of thorough cleaning in order to put it in a satisfactory and sanitary state”. The money was needed for “Cleaning out the cesspool and sludge chamber and carting away all sewage matter and trim sides of drains on sewage farm”.

Ultimately, the Army decided it was simply so bad, the best option was to vacate the building. When they did, nothing was spent to alleviate the problem and shortly afterwards the Bon Secours nuns moved out of the Glenamaddy hellhole bringing with them the surviving children, into a whole new hellhole; which until 1961 would be the Tuam Mother and Baby Home. There is no record of a penny being spent on the sewerage system, which was so bad that it drove the Army out.

Galway County Council records appear to be chronically unreliable in respect of this 'Home'. The record suggests that the Workhouse/ Home buildings finally were demolished by Galway County Council sometime in 1976. But there is substantial doubt as to the actual date. However, demolition was a cheap and shabby job. The Council simply cleared everything above ground leaving the cellars and tunnels of the Victorian buildings intact; covering them up with soil and rubble. Today much of that area remains covered by a playground for local children. In the Autumn of 1975 Barry Sweeney and Frannie Hopkins, two Tuam schoolboys then eleven and ten years old, climbed over a garden wall from where they had been picking apples and dropped onto an area just outside the perimeter of the old Tuam Workhouse.

Barry almost immediately broke through what seems to have been a thin concrete crust and fell into a pit or tank. To the horror of both boys this contained the skeletal remains of children. The area into which they had landed was part of the small parcel of land purchased from Captain Quentin Dick by the Guardians of the Tuam Workhouse in 1917. It was the place abutting the old Workhouse wall, onto which the sewerage of the Workhouse had flowed.

It was close to the spot where the Guardians had ultimately created a covered tank to replace the open cess-pit. This was the existing drainage system of the Workhouse buildings when they were re-invented as St Mary's Mother and Baby Home in 1925, deemed a threat to the health of the soldiers billeted there.

In 1937, Council works began on the same spot on an arrangement of twenty covered tanks as a drainage system to deal with waste from the 'Home'. It was here some fourteen years after its closure that the two boys broke open the cover of one of those tanks. to reveal the remains of infants.

On that Autumn day in 1975 the two schoolboys ran out of the place in terror as quickly as they could and told their parents what had happened. A local priest arrived and uttered some prayers over the spot. Galway County Council ensured that the cavity was thoroughly filled in and ultimately the area was grassed, walled and became known as the Children's Graveyard.

In 2021 this remains the only part of the former Tuam Mother and Baby Home which can be immediately identified as the burial site for some if not all of those 796 children registered by the State as having died there, but whose burial places are not recorded. As we know, no burial record exists except for just two of the Home children.

It is unlikely however, that true figures will ever be established. In the first place, 1,101, children are registered as having been born in the home, whereas the records of the Archdiocese of Tuam show 2,005 Baptisms carried out there, and remarkably this Register only covers the years 1937 to 1961, the years 1925 to 36/37, being missing. The number of children born in, sent to, dying in and “boarded out” of Tuam may never be known. Separate records kept by the Bon Secours nuns and the various arms of the State, now either, lost, withheld or destroyed, will never be subject to objective scrutiny. Prior to 1934, there was no statutory regulation whatever of such intuitions and even thereafter it was perfunctory (footnote 3).

Following the gruesome discovery in 1975, there was no newspaper or other media coverage. There was no Garda investigation or inquiry by the local Coroner. There was no debate in those eminent vehicles of local democracy the Tuam Town Commission or Galway County Council. In 1975, for a second time, the truth was quietly but firmly crushed under a covering of building site waste, rubble and soil.

Initially, concealment had been attempted through a plantation of trees by Galway County Council after the Department of Health closed the Home 1961, with a suddenness that took everyone by surprise. The plantation was carried out in such a specific manner and with such precise attention to the parameters of the hidden mass grave, there can be no doubt that the Council knew exactly what they were doing. The aerial photographs available in Military Archives put that issue beyond question.

Like the other Mother and Baby Homes and similar institutions the Tuam Home was a centre of human misery. Women were falsely imprisoned there because they had offended the morality of a deeply conservative and hypocritical society, which bent to the will of the Catholic Church. They had given birth to a child while unmarried. Their children were either used as currency to enrich the Religious Order entrusted with their care in a sophisticated human trafficking business, boarded out to rural farms often as child-labour, or if sickly, frequently allowed to starve and die in utter degradation.

While still living in the “Home”. Mothers and children were subjected to daily humiliation and abuse by the Nuns who controlled their lives. Many of the women were then transferred to other Church run prisons, the so-called Magdalene Homes. There, they were used as slave labour in industrial scale laundries to swell the coffers of their religious gaolers, many until the day they died.

Within just a few years of the horrifying discovery by two young boys in 1975, the ground surrounding the Workhouse/Home site was surrounded on three sides by a a newly built council housing development. This was the Dublin Road Estate. However, not even this transformation of the site could conceal the hellish history of the place.

The Tuam Home designated as St Mary's Mother and Baby Home had opened in 1925 in the rather dilapidated remains of the old Tuam Workhouse which had been empty for approximately three years. This and other 'Mother and Baby Homes', were a creation of the Local Government (Temporary Provisions) Act 1923, a new model of enslavement by the new intolerant Catholic State.

The Bon Secours Order now managed this institution on foot of a contract with the Local Board of Health and Home Assistance. In the absence of a centralised Department of Health, which did not come into being until 1947; this was in effect, Galway County Council performing that function locally. The contract meant that the sisters were paid a capitation grant for each mother and child it kept under the roof of the Home. The priorities of Church and State can be assessed by knowing that the original annual payment for the doctor appointed to the Home was £90, whereas the annual fee for the Catholic Chaplain was £150.

Whatever about the virtues of Dr Thomas Bodkin Costello, local worthy, antiquarian and by popular acclaim all-round “good-egg”; the appointment as Chaplain was a handsome additional income for a priest of the Tuam Archdiocese in 1925 and was of course charged to the public purse. There must be some doubt however, as to the regularity of attendance by Dr Costello given his extensive practice, notwithstanding his capacity to get about in his smart pony and trap.

There must also be some doubt as to his suitability for his post from some of his utterances with respect to infant mortalities and the death toll in Tuam. He is recorded as conveying the information that some fifty per-cent of children should be expected to die by the age of five. This information which he conveyed to the Local Board was reported contemporaneously in a local newspaper.

The only discernible role of the Chaplain to the Home, nominated by the Archbishop but paid by the Board was to baptise children born into the place. Apart from the burial records of two children registered as dying, no record exists to confirm that any other of those 796 children were given burial rites. But under church doctrine once given a splash of water by the Chaplain they enjoyed the salvation of being a Catholic and thereby 'saved' even if neglected unto death by starvation or lack of medical care in this Home.

The Tuam Home was not unique but was the only one operated by the Bon Secours Sisters. The biggest players in Mother and Baby Homes a joint business venture between the State and Religious Orders, were the sisters of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary.

While the Bon Secours ran Tuam, The Sacred Hearts ran larger parts of this Irish Gulag, at Castlepollard in Westmeath, Sean Ros Abbey in Roscrea Tipperary and the jewel in their crown, Bessborough, on the outskirts of Cork City.

The public record of the time, shows that the establishment of the Home at Tuam was driven by the need to close the existing wretched institution at Glenamaddy which operated as a quasi-orphanage and the wish loudly expressed by the then Archbishop of Tuam that its replacement be located in Tuam. The Galway Local Board of Health and Public Assistance, in reality the County Council in another guise, was happy to accede to his Grace's wish that this should be done.

The only issue was how much the good sisters of the Bon Secours should be paid to manage the Home. Despite the wide concern about the condition of the Glenamaddy Home and the conditions endured by the children in it and managed by the same Order of nuns, no question was raised as to their suitability to run the new Tuam Home.

Payment was to be by the numbers, a weekly sum for each mother and child resident in the Home. The more the merrier. How then was this Home to be filled? It was to be accomplished by the moral authority of the Church and Irish Society and almost every agency of the State.

They frequently arrived at the door, hounded out of their own homes by the Parish Priest, often in the charge of the Civic Guard, the police force of the State, having committed no breach of any law, to be handed over to the Sisters. They were also consigned there simply because they carried a child in circumstances of abject poverty, with no means of self-support. It mattered not at all whether they had become pregnant through rape, incest or simply as a consequence of vulnerability and ignorance and poverty.

Their visibility outside the walls of the Home was an affront to the Catholic sensibilities of the newly Independent Free State. In truth, they were the raw materials of a very Irish Industry. Part of the narrative of the apologists for this obscene and wholly illegal cleansing of society is that these women were free to leave at any time. This bilge has even been repeated in correspondence to the present writer by solicitors acting for a Religious Order.

The Report of the Department of Health for the years 1945-1947 places 'Unmarried Mothers and illegitimate Children' in a category of their own as distinct from the general population. At page Seventy-One of the Report it notes that the mother was free to leave the institution when their child was boarded out. Clearly the Department itself took the view that until mother and child were separated, the mother was not free to leave.

Ostensibly the rule was that the mother would remain as unpaid labour in the Home for a year and theoretically was free to leave after that time. Her child might be boarded out at the age of four or five to a family, sometimes effectively as a bonded agricultural labour. There was no mechanism for contact between mother and child, the mother never being informed where her child had gone.

The option of a mother and child leaving together was virtually impossible and Irish society would ensure that they could not survive together. In practice many mothers remained long past the notional one year of servitude within the Home. Many where transferred to an indefinite period of bondage at a Magdalene laundry. What financial arrangement or otherwise was reached between the various Orders in this transaction is unclear but everyone was a winner, except the mothers and children.

It is beyond question that the newly 'free' Ireland was committed to quite savage social engineering, an essential part of which involved sentencing its most vulnerable citizens to degrading servitude and from the creation of the Irish Free State, the chosen partners in this were the Religious Orders of the Catholic Church. It is useful at this point to try and join at least some of the dots. Church and State have and continue to resist the publication of such documentation not already lost or destroyed in respect of such institutions as Tuam and arriving at a clear picture remains difficult. The contemporary reports of local newspapers do sometimes help to fill in the gaps a little.

The Connacht Tribune newspaper of 21 January 1937 is helpful in this regard. On that day it reported; A petition was read out signed by a number of residents at Tobberjarlath, Tuam calling for the removal of the cesspool at the back of the Children’s Home, and in close proximity to a large number of houses occupied by the tenants of the Town Commissioners' houses. The petitioners' letter stated that the smell from the cesspool was intolerable and highly dangerous to the health of a large number of residents and their families in the localities....

No mention of or concern for the children and women imprisoned there is ever expressed.

A review of local newspapers for the previous twenty-five years discloses the same issues debated again and again during the period when the buildings served their original purpose as a Workhouse. The one common factor absent at all times is any recorded expression for the health or welfare of those confined within them either during its period as a Workhouse or a Mother and Baby Home.

So, in 1925, at the very loud urging of the then Archbishop of Tuam the old Tuam Workhouse was to become the Tuam Mother and Baby Home, a collection of building in such a condition that, it had to be evacuated by the national army. It is worth noting that while performing a similar task in Glenamaddy, the Bon Secours nuns, had overseen 80% of all infant deaths recorded in the Civil Register for the area, in 1923. No one of course raised any question as to the fitness of the Sisters of “Good Care” to be in control of the newly created Tuam Home.

https://www.gofundme.com/f/Justice-for-the-Tuam-Babies

To be continued.

Footnote 1: Dáil Eireann 14 March 1946 Questions on the progress by the Land Commission In the distribution of the Dick Estate.

Footnote 2: Military Archive, File 20/Buildings/282.

Footnote 3: I am indebted for this information, to the then Diocesan Secretary to the Archdiocese of Tuam Fr Fintan Monahan, now Bishop of Killaloe who provided it to me via email in September 2014