By Alison O'reilly For The Irish Mail On Sunday

A shocking recording from a woman who worked in an Irish home for unmarried mothers where almost 800 children died confirms there is an unmarked grave on the grounds of the infamous institution.

Julia Devaney entered St Mary’s Mother and Baby Home in Tuam, County Galway when she was nine years old and spent 36 years there until it closed in 1961. She worked as a domestic servant for the Bon Secours nuns.

Mrs Devaney gave a stark account of the home in a recorded interview with a former employer who ran a shop in Tuam some time in the 1980s. However, the tapes only resurfaced earlier this year.

From the 1920s, unmarried pregnant women in Ireland were routinely sent to institutions to have their babies, many of whom were sent to America for adoption.

Local historian Catherine Corless, who researched the names of the 796 children who died in the home from 1925 to 1961, has spent a number of months transcribing Ms Devaney’s interview.

Today, the Irish Mail on Sunday can reveal how Mrs Devaney said that children would ‘die like flies’ in the home. Mrs Devaney said: ‘Scores of children died under a year and whooping cough was epidemic. Sure they had a little graveyard of their own up there. It’s still there, it’s walled in now.

‘I don’t remember seeing any stillbirths. If the child died under a year, there were always inquiries. There wasn’t as much about it if the child was over a year.

‘Under a year old, the inspectors would put it down to neglect. They would look upon it as natural if the child was over a year because the child would be more open to diseases.

‘The nuns in the home did not condemn the women as sinners, no no. If the girls came in young, they were not allowed to finish their schooling. Nuns had very little contact with the children, they wouldn’t even know their names.’

Ms Devaney’s account of the sick children in the home supports a 1946 county board health inspection report that revealed how the children were ‘emaciated, fragile’.

The home, which was run by the Bon Secours nuns, was funded by Galway County Council. The inspection report also stated that dozens of children were described as ‘congenital idiots’ and were placed in a separate room, and mothers were only allowed to nurse their children for up to a year before they were adopted to the US or fostered locally.

She said: ‘The children were whacked at school, they had no sympathy any side, they had no one.’ Ms Corless believes the Commission of Investigation into Mother and Baby Homes should have a copy of the transcript, and plans to give it to Judge Yvonne Murphy, chairwoman of the commission, in the New Year.

The revelations on the tapes come after the Adoption Rights Alliance this week called for the terms of the investigation to be widened, to include other cases, such as those from private orphanages.

Ms Corless said: ‘Julia was in the home all of her life, she knew what happened there.’

In May 2014, the MoS brought the story of the 796 children buried in an unmarked grave on the site of the home – where a housing estate is now built – to international attention.

While the story was met with outrage, a number of later reports claimed there was ‘no evidence’ of the children’s remains. This is despite a number of eyewitness accounts of bones found on the site.

The testimony of a woman who spent most of her life in the home adds crucial new evidence about the existence of the grave, and what the Bon Secours nuns and the council knew about the situation. Ms Devaney, who died around 20 years ago, was a respected member of the community in Tuam.

She was born in 1916 and as a baby she was placed in a ‘children’s home’ in Glenamaddy. She moved to the Tuam home in 1925, where she remained until it closed in 1961.

When the home closed, the nuns gave her a job in the gardens of the Grove Hospital, which they also owned, until she married John Devaney.

The couple lived out their days in Gilmartin Road, Tuam, and Mrs Devaney gave an interview to one of her gardening clients, who owned a shop in the town.

The Mail on Sunday has published extensive extracts from her interview that reveal she believed the children were ‘never cared for’. Ms Devaney, who never had any children of her own, constantly refers to the orphans in the home and how it was apparent to her that they meant nothing to the nuns.

She said it was a ‘horrid place’, which was ‘cold, sad and loveless’: ‘It was not like a home, they’d be better off with a drunken father at home. It was an awful lonely old hole. Not natural, unnatural.

‘The children had a language all their own, they didn’t talk right at all, nobody to teach them, nobody to care. When the children came home from school they got their dinner and then their hair was fine-combed for nits and fleas.

‘They got tea, bread and butter and cocoa for their supper. The little ones went to bed summer and winter at 6pm.

‘They had swings and see-saws, but when I look back they were very unnatural children, shouting, screeching.

‘When the home closed and the children were all gone to Roscrea [Seán Ross Abbey] they were all taken away in vans and ambulances.’

She also describes how in the 1950s dozens of children were adopted to the US.

It’s understood many of these were illegal adoptions with families still trying to trace their loved ones because of the lack of proper paperwork.

Mrs Devaney described how one sister did not like the children going to the US: ‘Sister Leondra would say, “Why should we be rearing our Irish children for America?”’

The Children

Julia spoke about the loneliness the children experienced and how they received little or no attention. She reveals shocking details of horrifying neglect and sicknesses. The children had a language of their own and were constantly ‘wailing and crying’. Years after the home closed Julia believed she could still hear them when she visited the site.

‘The Home children were like chickens in a coop, bedlam, screeching, shouting in the toddlers’ room. They never learned to speak properly, ’twas like they had a language all of their own, babbling sounds!’

‘The children had a language all their own, they didn’t talk right at all, nobody to teach them, nobody to care. When the children came home from school they got their dinner and then their hair was fine-combed for nits and fleas. They got tea, bread and butter and cocoa for their supper. The little ones went to bed summer and winter at 6pm.’

‘The nuns were very regimental with the children, doing drills and ring-a-ring-a-rosy with them.

They made no effort to develop their minds. The mothers were told to feed them and clean up after them and put them on the pots. I think they spent most of their time sitting on the pots.’

‘The children were so mischievous that they would throw the pots and blankets out the window just for something to do.

Boys left the Home at five years of age and the girls at seven years.

I always noticed that the children were awful small for their age. Always undersized children.’

‘Some of the children wouldn’t use spoons, but use their fists to lift the porridge out of the mugs, and they would get a whack.’

‘There were never any toys or books, never any effort to teach them anything. I’m sure a lot of them are in mental homes now…’

‘Nobody loved the children…’

‘The children would be trying to get up on your knees and trying to love you, looking for affection.

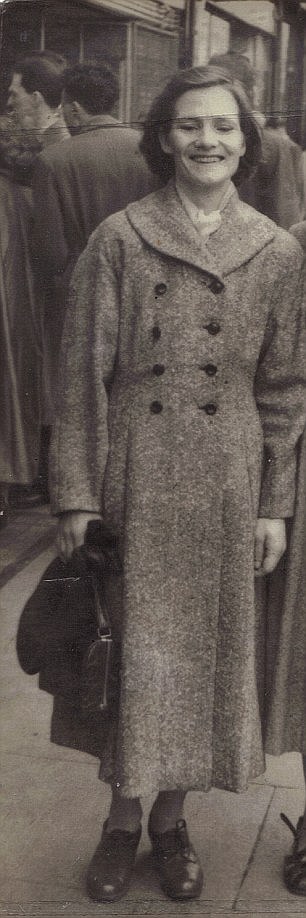

Bridget Dolan, pictured, had two sons placed in the home. One died and there is no trace of the second. He may have been illegally adopted in AmericaThey were very backward, everyone they saw on the road was “daddy” and “mammy”, because they would hear other children in school talking about their mammy and daddy.’

Bridget Dolan, pictured, had two sons placed in the home. One died and there is no trace of the second. He may have been illegally adopted in AmericaThey were very backward, everyone they saw on the road was “daddy” and “mammy”, because they would hear other children in school talking about their mammy and daddy.’

‘I have terrible regrets for the children, I feel a sense of shame that I did not create a war, but then again what could I have done?’

‘It makes me lonely when I walk up to the Home site now, I think I can still hear the Home children shouting and laughing.’

The nuns

There were more than 20 nuns in the home while Julia was there. She gives detailed insight into how they made their own rules and bizarrely gave a girl called ‘Bina Rabbitte’ a lot of control. Her name was used on every Birth, Baptism and Death Cert, as ‘Assistant Matron’ when she was just a domestic. Julia remembers every nun – some exceptionally kind, others were ‘devils’.

The Good

‘Mother Hortense … She was a big hefty woman, a slave driver with a heart of gold. She was friendly, but still she put those poor girls into Ballinasloe and the Magdalene laundry!’

‘Sister Priscilla was childlike … There was a lovely old nun in the home long ago, a Sr Priscilla and I would canonise her, she hadn’t much to do with the children, she was old but worked with the chapel and the convent side of it. But she was the essence of kindness to everybody.’

‘Sister Anthony would say to the women, “Don’t be crying, wouldn’t it be worse if it was a bad marriage?” Sister Gabriel, in charge of the babies, was always praying.’

‘Sister Patrick was a lovely nun, she was elderly, she would walk down the garden to me as she said she hated being above in “that place”, and she would always be telling me her love stories. She was natural… the only nun who ever spoke to me about life as an equal.’

‘There was a beautiful nun, Sister John Baptist, she was magnificent, and they sent her up to the children’s home to try her vocation, and by God she left it. She left the convent!’

‘Sister Celestine was a bit peculiar, whatever thing she had about clean clothes, she used to change her clothes on a Saturday night, and take all she took off her and burned them in the furnace.

She was daft. She started the 1p dinners in Dublin. A little red-faced woman. Sister Celestine was red faced from washing herself.’

‘One nun in the home, Mother Ann was the most beautiful person – she wouldn’t see a hole in a ladder. She ruled by gentleness, she’d do with love what Martha did with an iron rod. She was the nun that closed the door in the home in 1961.’

‘Sister Leondra did not like the idea at all of the children going to the USA. “Why should we be rearing our Irish children for America,” she used say … Then there was old Sister Leondra from Belfast who was sent to Tuam, and her sister, Sister Camilus who was sent from Cork to Tuam. They were probably sent here to die together, and are buried in the Grove grounds now.’

The Bad

‘Mother Martha … She ruled us with an iron hand. She had a set on us women that grew up in the home under Mother Hortense. She’d keep you down. On a wet day when I couldn’t go out on the land, I might go inside and maybe do a bit of crochet, and my heart would be in my mouth for fear Martha would walk in.’

‘Martha… life wasn’t worth living with her.… You couldn’t argue with her, she would give you a thump to put you into the middle of next week!

The Women

The women who were unfortunate enough to end up in the Tuam home were often left shocked by their experiences while a number of them were committed to Ballinasloe psychiatric hospital. They became increasingly frustrated and devastated, and often took their anger out on the children by beating them. Julia recalls their daily routines and how she befriended a number of women.

‘The women had to have an admission ticket from the doctor to get in. There was no such thing as being signed in, but once they were there they would have to wait a year to look after their baby. One girl escaped, went out, but she was brought back again that night by the guards.’

‘Breakfast consisted of porridge, milk, tea and bread – trays of bread. Then down to feed the babies.

Children went to Mass, too. The children got porridge, milk, bread and tea before school.

Mothers then fed their babies, they were barged into breastfeeding. If the babies weren’t breastfed, bottles would have to be made up and sterilised. She’d [Reverend Mother] nearly starve the infant to make the mother breastfeed. The doctor had to certify that the mother could not breastfeed before bottles were given.’

Catherine Tully, pictured, was born in the Tuam home. Her mother died shortly afterwards and was buried, secretly, in her grandparents grave, which she only recently discovered.

Catherine Tully, pictured, was born in the Tuam home. Her mother died shortly afterwards and was buried, secretly, in her grandparents grave, which she only recently discovered.

‘The mothers used to belt the hell out of the little children and they could be heard screaming by passers-by on the Athenry Road. Probably mothers frustrated and taking it out on the other children.’

‘None of the women ever attempted suicide. They had a very hard life, there was no consolation, no advice, no love there for them. They just got through, counting the days and weeks until they were free to go. The parents would come back to the home to bring the woman out after her term of a year was up, whether it was to put them on the train or what, and the nuns would get a job for anyone else who had no one to meet them.

Sometimes people from Tuam would come up looking for a servant girl.’

‘The mothers would never tell me anything. They were afraid of the nuns and they were suspicious of us, even though I would be nice to them. They were always talking amongst themselves. The garden wasn’t hard for me for I loved it, but the girls were unhappy at it. It was an unhappy ould place, that’s what it was now. The girls found no interest there, they were just putting in the day.’

Julia

As the last resident to leave the Tuam home after the children and mothers were shipped out to Seán Ross Abbey in Roscrea, Julia has given a stark account of her life there. Her interview is laden with the impact the home had on her as a person. She explains how she always felt inferior to everyone else, and was excluded in class when other pupils were asked what they did for their summer holidays.

Her only avenue of escape from the home was when widower John Devaney – a County Council worker who had done jobs at the home – asked her to marry him. She accepted his proposal.

Julia Devaney arrived at the home as a nine year old and worked there for 36 years until it closed in 1961‘I never thought about not having parents … Parents didn’t enter the head of the children because you never miss what you didn’t have. You would know you had no one and just get content with that.

Julia Devaney arrived at the home as a nine year old and worked there for 36 years until it closed in 1961‘I never thought about not having parents … Parents didn’t enter the head of the children because you never miss what you didn’t have. You would know you had no one and just get content with that.

‘I wasn’t bright in school because you were made stupid from the environment you were reared in.’

‘I always had an inferiority complex, I’d be thinking I shouldn’t get the same as everybody else.

If I was at the Post Office, honest to God, I’d let another in before me, even to this day and I an ould hag!

I’d even think the priests would know, and they would just shun me on account of that. I think the children who were fostered out fared better.’

‘The nuns never taught us the facts of life, I don’t know did they even know themselves. It was only in later years that the Bon Secours Sisters were allowed to do maternity. We were not told about periods, they did not even give us a sanitary towel or a bra or anything.

When I got my first period, I used to be hiding it, I used ould cloths and rags, there was plenty of them around. I had learned what to do from the women.’

‘John Devaney started chatting to us, and then he told me his wife Delia had died three years ago and that he had a fine empty house, and that he would take me out of there if I would marry him!

He then asked me if I would go to the pictures with him on Sunday night, and I said I would go the following Sunday night.

So he said okay and then said he would go and get a packet of sweets for me. [We put] dish cloths in our mouths to stop us laughing so the nuns wouldn’t hear us.’

‘[A domestic servant] Bina was in charge with a bunch of keys, you wouldn’t dare go out that gate. You were conditioned that there was no other life but this. We would never, never, never be let out to a dance.

[Named woman] might invite us to a film at the cinema and we might be let out to that. We never questioned it, we were conditioned.’

Catherine Tully, pictured with daughters Christina and Teresa, did not leave the Tuam home until she was five.

Catherine Tully, pictured with daughters Christina and Teresa, did not leave the Tuam home until she was five.

‘The nuns took a house down by the sea in Achill every summer for a month or six weeks.

We would take it in turns to spend a week with them. [Named woman], the nuns’ cook, and myself, and [named woman] and the other domestics.

A yearly treat. It never dawned on us that the nuns were wronging us and that we were entitled to our own lives.

It was later when new nuns came to the home that they asked questions and why us grown women were still in the home.’

The Home

In the interview, Julia spoke often about the home, how it looked, felt and smelt, as well as about those who came through it during its 40-year existence. She claimed that around 2,000 women passed through the home and gives clear descriptions of many of those unfortunate unmarried mothers. As Julia puts it, there were three kinds of people in the home: ‘Us, them and the nuns,’ referring to children, mothers and the nuns.

‘It was a cold, sad, loveless place, not like a home, they’d be better off with a drunken father at home.

It was an awful lonely ould hole. Not natural. Unnatural. ’

‘They knew well that the home was a queer place, ’twas a rotten place. The poorest downcast family were better off than being in the home – there’s love in the family home even though there’s poverty.’

Catherine, left, pictured with her daughter Teresa, never knew until recently where her mother was buried.

Catherine, left, pictured with her daughter Teresa, never knew until recently where her mother was buried.

‘There was approximately 50 women at a time in the home. The place was spotless, a show case like the Botanical Gardens. All the women spent each Saturday sweeping the yards. The women did as they were told, most of them gave no trouble, the ones that did give trouble were sent to Ballinasloe mental hospital, St Brigid’s. Some women would get into fights with others, they were so frustrated. The doctor had to certify for women to be sent to St Brigid’s. The doctor would do what the nuns told him, without question. That’s how the row was settled!’

‘The home was the worst institution as regards human rights!’

‘It was like a secret society in the home. You were content ’cos you knew no better. We were allowed to go out and vote, we were told who to vote for. We were told to vote for Fianna Fáil, of course. We never rebelled, we had no mind of our own. You did what you were told.’

Recreation

Despite being a home for unmarried mothers and their children, there were no toys in the building. The children played ring-a-ring-a-rosy but never had one-to-one attention – the nuns often forgot who they were. The mothers sang or played cards, music was a thrill for them because they had no experience of the outside world and those who did go to school, were mostly ignored by the teachers there.

‘In St Brigid’s hall in the home, they used to have a melodeon and the women would chat and laugh and play cards – a drug to help them forget!

On bonfire night they would listen to music coming in from Tubberjarlath Road. I remember [named woman], a lovely girl. Wooden Heart was a song out at the time, and she would stretch her neck out the window to hear it.’

‘They used to have plays at Christmas time … We had great plays. There was a stage, like, down in the town hall. The Grandfather Clock was one of the plays we did. The doctor’s family would come up to see it, and [named woman] [whose] father came from the same place in Co. Clare as Mother Hortense.’

‘I remember a blessed statue out where they were playing. There were swings and a see-saw. Then there was a turf shed and the bottom of the door was broken, and the children used to gather up bits of turf and fling them at the statue.’

‘There was an elderly woman in her forties who had a baby, she had a grey head.

She was a great violinist and could dance as well … Her music brought happiness to the children.

‘They had swings and see-saws, but when I look back they were very unnatural children – shouting screeching sometimes laughing Ring-a-ring-a-rosy.’

Deaths

While there has been much debate regarding the Tuam grave and whether or not the children are actually buried there, Julia – a former resident who was the last person to leave the home – describes the grave in great detail and how ‘it’s still there’ except it’s ‘walled in now’.

Our story in the MoS in May 2014 revealed how 796 children were potentially buried at the home after burial records could not be found for each and every child.

‘Children died of measles, there were no antibiotics. Dr Costelloe was a very old doctor, scores of the children died under a year and whooping cough was epidemic, they used to die like flies.

Sure they had a little graveyard of their own up there. It’s still there, it’s walled in now.’

‘Some of the mother’s didn’t like their own child, you would have to watch them, maybe they wouldn’t give the child the bottle at all.’

‘I don’t remember seeing any stillbirths. If the child died under a year there were always enquiries.

There wasn’t as much about it if the child was over a year.

Under a year old, the inspectors would put it down to neglect.

They would look upon it as natural if the child was over a year because the child would be more open to diseases.’

‘A [named mother] girl took it to heart terrible that she was placed in the home. She had no energy and stayed in bed for six months and kept a glass of milk beside her bed. She was so lonely. When her child was born she was there waiting, waiting for family to call.

She died when the baby was six days old. She died of a broken heart. When she died her family came in for her. The nuns told the family that they should have kept contact while she was alive.

Twas nearly the closing of the home.’

The Locals

They were known as ‘home girls’. Julia remembers how the locals would threaten their own children with putting them into the home if they misbehaved. She also knew that the shock of living in the outside world would be enough to leave some residents in a psychiatric home.

‘I always felt that the outside world had an edge on us, that they looked down on us. You’d feel you couldn’t cope with the outside world … Families outside used the home as a threat on their children, that if they didn’t behave, they would be sent there.

‘The nuns would tell us not to be talking to local people in case they would be asking questions about the home. We were totally cut off from the outside world.’

‘I was never asked to any of the schoolgirl’s houses, we were always looked down on. I still feel that people look down their noses at me. I wouldn’t like the Gilmartin Road people [where Julia came to live] to know I came from the home, I wouldn’t like it.’

‘I don’t remember the town’s people coming in to give birth. If they did, we would not see them. They might be “spotted” all right. Their people wouldn’t go in, because it would be too conspicuous and even if they were seen going up the Dublin Road, ’twas enough to say they were in it...’

‘… she heard the two of them saying, “that’s a home wan.” Now, they must have heard it from their parents – “that’s a home baby” – that’s what they said. And she felt awful sensitive about it. That’s what they used to call us, not in my time, but later – “the home babies” – no matter what age you were. We were never invited to anyone’s house.’

The Men

Men on the outside rarely spoke to the women once they went into the home. However, Julia explains that the workmen or delivery men would be friendly to the girls and often asked for their hand in marriage – an escape for many of the women. The men did not take their babies though.

‘The mothers spoke only to each other about the fathers of their children. They’d hate to face home. The lads that were friendly with them outside would ignore them now. Many a girl shed tears – a terrible depressing place.…An odd fella would come in and take the girl out and marry them. I remember one case where the parents and the priest and the fella came in and said he would marry the girl. He went down on his knees but he would not take the child as it was not his.’

‘[Named woman] was a very pretty girl when she was young, and when we were brought down to the Corpus Christi procession, there was a man, he was a clerk, and he fell in love with [her] and she used to steal down to the gate at the home to see him … [Named woman] was about 21 and if they had been left alone, that man would have married [named woman]. … It broke [named woman’s] heart.’

‘John [Julia’s husband]… was an ould man but he was kind. I thought I had stepped into heaven when I first went into the house. Everything looked so small, the kettle and pots, I was used to big saucepans and huge tea pots. John bought the messages as I had no idea how to use money and he also did the cooking as I never learned to do that. I was totally institutionalised.’

The Work

The work carried out by the women was ‘tough and endless’. While Julia said she took to the garden in order to keep her sanity, the other women all had their own jobs digging land, cleaning, cooking and ironing. They were not paid. Money was allegedly put into the post office for them – which they never saw.

‘… The mothers went to the laundry to wash the babies’ nappies … a big bath of cold water for dirty nappies. Each mother had to account for their own nappy …

They’d each go to their jobs after that... go out on the land digging, or the kitchen, scullery, dining room, children’s dormitory.

Polish and wash and clean, make the beds, monotonous work.’

‘In the morning they would take the “mackintoshes” off the beds, clean and dry them by hanging them on the old iron stairs.

Then at 5pm they would put them back on the beds. The children would be taken out at night to the toilets but if they were taking them out forever, they would still be pissing the beds. The smell of ammonia was all over the place!’

‘I dug the garden in winter for it to be ready for March. We dug with spades and shovels for drills.

Six girls helped out with the digging. The women were listless, they had no interest in the work they did in the home. They were told they were there for penance, and they knew there was no way out.

They knew they had to hide from the outside world, they were not wanted out there.’

‘It was more like a prison climate there, there was never a feeling of nurse/patient attitude.

About 2,000 women passed through the home in its lifetime.’

‘I was out on the land, it wasn’t as monotonous as inside. We had chickens, pigs, and I cleaned out the sheds and spread the manure on the land.

I cleaned out the glasshouses and put in fresh clay.

We had a little ass and cart bringing out a pile of manure to the different gardens.’

‘The dormitory floors were done with beeswax blocks.

The children’s play area had to be scrubbed each day.

It was a big long room with toddlers and the smell of urine would come from the wooden floors. I had nothing to do with the children. Supper was at 7pm and the women were free after that.’

The Magdalene Laundries

The Magdalene Laundries were institutions, generally run by Catholic religious organisations that operated for more than 200 years from the 18th century to the late 20th Century. In Ireland the first was founded in Dublin in 1765 and the last closed in 1996. They were established to house unmarried mothers. An estimated 30,000 women were confined in these institutions in Ireland.

Julia describes them – along with mental institutions – as the ultimate punishment for women in the homes.

‘None of the mothers would kick up, because if they did, then they knew they would be put into the Magdalene, they’d be punished. It’s a place you wouldn’t want to make too much talk about your child, it’s a place you’d want to be very careful of what you’d say or you would pay for it. … If children came back from being fostered out, and if they were a bit slow, they would be sent into the Magdalene Laundry as well.

I know of four that were sent in, they are there yet. If women had two children, they were sent to the Magdalene Laundry. If they were wild outside, the priest would send them into the laundry. Most of them were country girls who might get into trouble working for big farmers.’

‘It wasn’t only mothers who were sent to the Laundry. Say children who were sent out into the world and they weren’t a success, they would be sent to the Laundry instead of trying to make something of them. That’s what they’d do.’

‘I know of three of them [children from the home] who came back with illegitimate children themselves, and I don’t think that they ever got out again.

They were put into the Magdalene Laundry. I visited the Magdalene Laundry once to see some former residents, and a nun came in and she addressed everyone as “Maggie” – they didn’t even have their own names any more. In later years the Magdalene Laundries were closing because the townspeople were opening their own laundries and St Mary’s was running out of penitents. The women I visited were very institutionalised and were praying like the nuns.’

The Interviewer

The interviewer Rebecca Millane, also known as ‘Rabbi’ is from Tuam and ran a shop in High Street. Julia was employed to do some work for Rebecca and between them they decided to do an interview.

However the interview was never broadcast or published until now. It was only through local historian Catherine Corless’s tireless work highlighting the plight of the Tuam babies that the tapes have surfaced. At a time when people feared and obeyed the Church, Rebecca was not afraid to ask the question why these children were discarded and treated so badly by people who claimed to be followers of Christ. Julia’s response lays bare the legacy of the Tuam home.

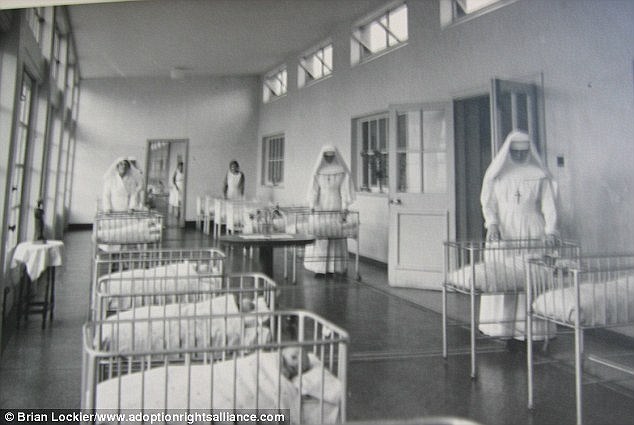

This picture from the early 1920s shows some of the first children to be detained in the home

This picture from the early 1920s shows some of the first children to be detained in the home

‘Well, they weren’t Christ-like that’s sure. There was not justice to the children – not at all! They were left to fend for themselves – at five years of age. They walked up that front path with a nurse to the ambulance with all their worldly possessions, with a pair of heavy booteens and socks and a new coat and a change of clothes, and that was their worldly possessions going out into the world and we’d never see or hear of them again.

I used to feel so sorry for the little child when the mother went out into the world.

They were like chickens in a coop, all reared in a batch.

I don’t know how they adjusted at all to the world.

Oh it was an awful place altogether to be for any child. I’d say it left a mark on them for life.’